Western culture today equates the pursuit of happiness with seeking out pleasure and comfort. But without the pursuit of experiences and goals that entail a certain degree of suffering, our lives would be meaningless, argues Paul Bloom in this interview.

The fundamental thesis of your new book, The Sweet Spot: The Pleasures of Suffering and the Search for Meaning, is that suffering is necessary for a happy and meaningful life. Why do you think that claim can come as a surprise to some?

Many people, including many psychologist colleagues, think that we are hedonists—that pleasure is all that matters. If this is your perspective, then the importance of suffering can get missed.

Now a smart hedonist can concede some role of suffering—maybe suffering now leads to more pleasure later, and the math works out so that choosing the suffering is a smart move for someone who only wants pleasure. But I argue that suffering gives us more than pleasure, and more than happiness; that it is central to goals we have that are entirely separate from those of pleasure and happiness. This refusal to treat pleasure/happiness as the sole goal of life is a surprise to some (though, as I point out in the book, old news to many others, particularly those steeped in religious tradition.)

___

Some people, especially in the modern West, think that all that matters for a good life is pleasure. One purpose of my book is to argue against this.

___

Has western culture misunderstood happiness to mean comfort and joy? What do you think the source of this misunderstanding is?

Everyone seems to use the word “happiness” in a different way, and I’m cool with this. I don’t think that someone who equates happiness with pleasure is making a mistake; they simply have their own definition.

So here’s a different way to frame my view without that annoying word. Some people, especially in the modern West, think that all that matters for a good life is pleasure. One purpose of my book is to argue against this, to defend what’s been called motivational pluralism, which is the view that people want many things. We want pleasure, of course, but we also want to have meaningful lives, to be morally good, to have intimate relationships, to enjoy a range of experiences, and much else.

SUGGESTED READING

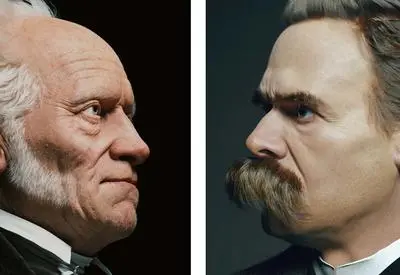

Schopenhauer vs Nietzsche: The meaning of suffering

By Joshua Foa Dienstag

SUGGESTED READING

Schopenhauer vs Nietzsche: The meaning of suffering

By Joshua Foa Dienstag

You say our culture suffers from a fetishization of pleasure. But is it not also true that Western culture, particularly the economic structure we live under, also fetishizes achievement? And is there not a risk in telling people that they have to suffer to live meaningful lives, when they live in an economic system that benefits from suffering (for example, the overworking of employees)?

I think there are some interesting issues here, but I should emphasize that I am not overall in favour of suffering. Most suffering is awful. My book is a defence of chosen suffering, everything from hot baths to BDSM to scary movies to training for a marathon to having children. Involuntary and unchosen suffering of the sort you’re talking about is totally different, and I think—contrary to some—that there is little to be said for it.

I will add, though, just to challenge a premise of your question, that by every possible measure, the citizens of communist countries are miserable and unfulfilled. People seem to flourish the most in societies that have some degree of market capitalism, though also with strong support for those at the bottom of the ladder.

Join the conversation