Beneath the headlines about Trump’s ambition to take Greenland lies an even more troubling story of brewing superpower conflict in the Arctic. Award-winning journalist Kenneth Rosen argues that years of American failure and ineptitude in the polar north have left it defenceless there against China and Russia, at a time when a warming climate makes the region more strategically crucial than ever.

One could be forgiven for thinking tensions in the Arctic, perhaps most prominently embodied by President Donald Trump’s egregious campaign to “get” and secure Greenland as another American territory, came out of nowhere. But it did not. Historically, the American desire to control Greenland has existed nearly as long as America itself. It was not Trump’s rhetoric of a takeover that struck me during my years spent traveling and reporting on the circumpolar North. It was the ineptitude surrounding the idea. To publicly make threats of invading Greenland while America continually fails by all metrics in the Arctic, at home and abroad, seemed anathema to our own desires and lacking abilities across the region. To those of us who have been watching the Arctic over the last half-decade or so, the possibility of conflict in the Arctic now feels inevitable.

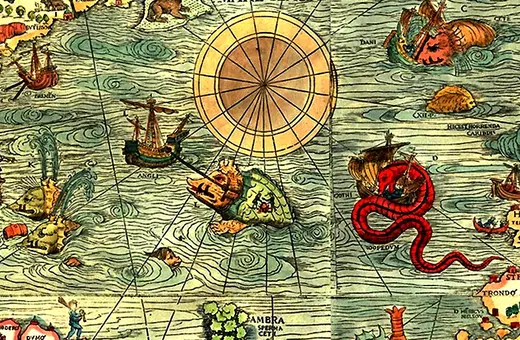

The Arctic will always remain important for the same reasons it stays with those who find themselves susceptible to its otherworldly influence, viscerally clinging to those who accept its omniscience no matter one’s distance from the geographic North Pole, and especially no matter their politics. The subject of the Arctic, its permanence atop our world, seems to return with greater frequency each day.

___

The first cars and ships and planes ever brought to Greenland arrived thanks to the Americans.

___

On Greenland Air 628 from Upernavik to Qaanaaq, the island nation’s northernmost village, passengers are now friendly. They first met on the flight from Kangerlussuaq to Ilulissat, then again on the flight from Ilulissat to Upernavik. They are not visitors to the Arctic. They are coming home. The plane is a twin turboprop, its variable-pitch propellers transitioning on takeoff and touchdown for granular airspeed control. The engines whine and moan. At 20,000 feet, the cabin lights flicker on, then dim.

Through the plane’s window, there’s a starry firmament overhead, with the polar winter one long night. In the southwest, a flash of sun. On a clear day or night, the American military base is visible on approach to Qaanaaq.

The base’s lights illuminate nothing but a smattering of buildings and the airstrip, a reminder of Arctic legacies and footprints, of how time is the great unrepentant equalizer. Supporting growth and opportunity only to abandon it has been the American calling card in the greater Arctic for decades. America’s derelict ambitions in the Arctic are readily apparent across all of Greenland. At least since the mid-nineteenth century, the United States has been bullish on Greenland’s potential to be an Arctic surrogate for national defense. Then, between 2010 and 2020, those ambitions evaporated and with them went America’s literal and figurative footing across the region, its ambitions overwhelmed by its inabilities against nature and foes alike.

Join the conversation